A Nation's Invitation to the World: The Story Behind Japan's Extraordinary 1954 Travel Guide

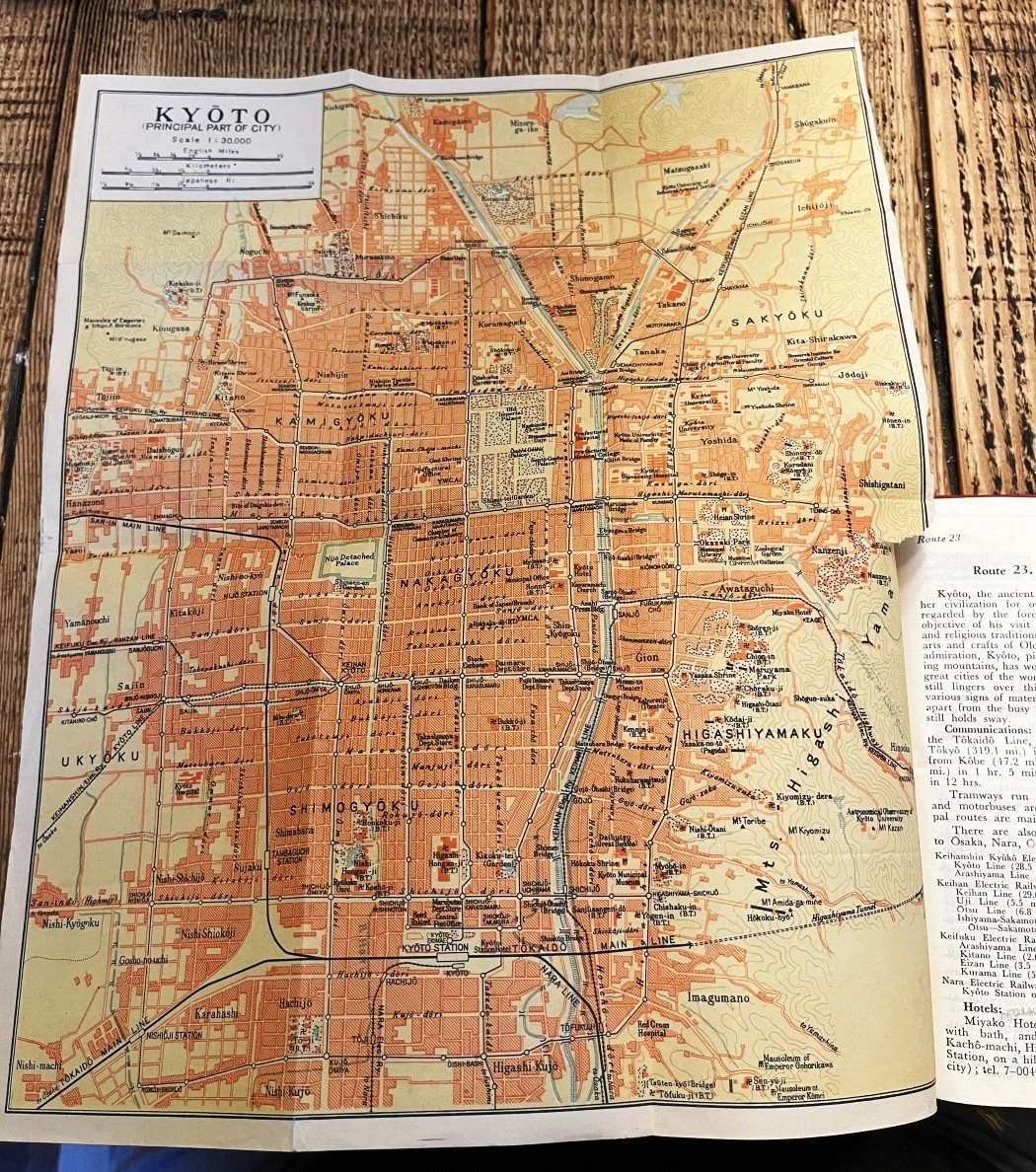

One of the reasons I love old book stores is to think through the history of how each book ultimately came to be published. I was lucky enough to find a weathered volume of "Japan: The Official Guide" tucked away in a corner for sale at the Parnassus Book Service in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, that really peaked my interest. This particular book published in 1954 by the Japan Travel Bureau tells an extraordinary story. At over 850 pages thick and featuring more than 60 meticulously detailed fold-out maps, this wasn't just a guidebook—it was a declaration of hope, an act of profound courage, and perhaps most importantly, an invitation extended to a world that had every reason to turn away.

The Weight of History

To understand the significance of this guide, we must first consider the Japan of 1954. The country was emerging from the ashes of defeat, occupation, and international isolation. The atomic bombs had fallen on Hiroshima and Nagasaki just eleven years earlier. American occupation had only ended in 1952. Much of the nation's infrastructure lay in ruins, and Japan's reputation on the world stage remained deeply scarred by the events of the war. Yet someone at the Japan Travel Bureau looked at this devastated landscape and made an extraordinary decision: they would create the most detailed, most welcoming travel guide the world had ever seen. They would open Japan's doors not with hesitation or apology, but with unprecedented thoroughness and genuine enthusiasm.

The sheer ambition of "Japan: The Official Guide" is breathtaking when viewed in historical context, with extraordinary detail not only on the major cities and famous temples, but also on every worthwhile destination across all four main islands. Those 60-plus fold-out maps required painstaking cartographic work, often of areas that had been recently rebuilt or were still under reconstruction. This was more than tourism promotion—it was an act of faith in Japan's future. The guide's creators were betting that the world would want to visit Japan, that foreign travelers would be curious about Japanese culture, and that the country could transform itself from a pariah nation into a destination people would actively seek out.

Imagine the teams of writers, cartographers, photographers, and researchers who brought this guide to life. Many of them had lived through the war, perhaps lost family members, certainly witnessed their cities reduced to rubble. Yet here they were, methodically documenting hot springs in remote mountain villages, mapping out temple visits, describing the subtle differences between regional cuisines.

These weren't government propagandists trying to whitewash history. The Japan Travel Bureau was genuinely attempting to share what they loved about their country with complete strangers. Every fold-out map represented hours of surveying and drafting. Every restaurant recommendation came from personal experience. Every cultural explanation had to bridge vast differences in customs and expectations.

A Window Into a Transforming Nation

The 1954 guide captures Japan at a pivotal moment—no longer the militaristic empire of the 1930s and 40s, but not yet the economic powerhouse it would become in the following decades. It documents a nation rediscovering its identity, deciding which traditions to preserve and which to evolve, all while extending a hand to the international community. The guide's very existence suggests remarkable optimism about human nature. Its creators believed that if they could just show the world the Japan they knew—the one with sublime gardens, profound spiritual traditions, and warm hospitality—visitors would be able to see past the recent darkness to appreciate the culture's deeper beauty.

"Japan: The Official Guide" was part of Japan's broader effort to reestablish itself as a welcoming destination and demonstrate the nation's commitment to international engagement. Those 850 pages and 60 fold-out maps contributed to laying groundwork for what would eventually become Japan's thriving modern tourism industry, which today welcomes millions of visitors annually. But perhaps more importantly, the guide represented something profound about human resilience and hope.